A J.E.C. Rasmussen painting Displayed at the Nuuk Art Museum

Lately, race relations have been front stage in the United States. For the most part, I try to listen and reflect on my role. As part of that reflection, I wrote this a while back, and I thought I would share

Racism comes with all kinds of baggage, and I think addressing it is crucial in our path toward a new, better world. In my experience, culture and race are often connected, if only in the form or heritage. With that, cultural appropriation can be used to demean a group of people. I also think celebrating culture is a powerful way to raise up groups of people. I hope writing this article can help to briefly highlight the evolution of kayaking, and the cultures kayaking came from.

I definitely agree that many examples of cultural appropriation are offensive. I also acknowledge that humans have different cultures because culture continually evolves. I do not come from an underprivileged demographic. Still, I believe respectfully embracing traditions and culture can be a technique to bring people together.

Kayaking is not often considered cultural appropriation, but it is a tradition adopted from another culture, so by definition, it is. With that in mind, I want to acknowledge I have adopted kayaking into who I am, and pay respects to the culture it was taken from.

Kayak is a word from indigenous arctic people, primarily in the North American arctic. These communities are widely known as Inuit, though, different regions referred to themselves differently. Some of these names include Kalaallit, Tunumiit, and Inughuit. Kalaallisut, of the Kalaallit, is still commonly spoken by the small population of Greenland (around 58,000). The languages originally did not have a written form, so it can be spelled in many ways. Before "kayak" became the standard spelling, "kyak," "kayack," "caiack," or "kaiak" were all options. In Greenland kayak is still spelled qajaq.

A J.E.C. Rasmussen painting Displayed at the Nuuk Art Museum

Traditionally qajaq would be a single kayak, while qaannat would be plural. However, the differentiation did not bridge the gap into English. Today, qajaq is only used to describe a true Greenlandic kayak. Qajariaq, meaning "like a kayak," would describe the plastic and composite boats commonly paddled. The word kayak directly translates to “hunter's boat.” Interestingly, in Greenland, I learned kayaks were not thought of as boats but more a prosthetic extension of self. A kayak would be built to fit a hunter based on ratios between their body and the boat. Each community developed unique designs for their kayaks based on the conditions where they paddled.

Skin-on-frame Kayaks Outfitted for a Hunt at the Nuuk Art Museum

Resources in the Arctic are limited even now, but the main materials available came from the sea as driftwood originating in Siberia and the creatures. Greenlandic people moved with the seasons, following food sources. In the summer, they traveled to hunting villages with the entire community in kayaks and uminaks. An uminak is a large open top boat that directly translates to "family boat." Like kayaks, they were constructed with skin, wood, and bone.

Uminak Frame Displayed in the Nuuk Art Museum

Young men had to earn the right to paddle a kayak—part of the process involved learning to roll on ropes. Kayakers were stitched into their kayak, so if they could not roll, they would be forced to cut themselves out of the kayak, and risk hypothermia and drowning. The rolls in the boats were developed to respond to different positions one might be flipped into while hunting. These skills are primarily used for rolling competition now, but the rolls are all transferred from skills that could save a hunter's life.

Kayak Rolling Demonstration in Sisimiut, Greenland

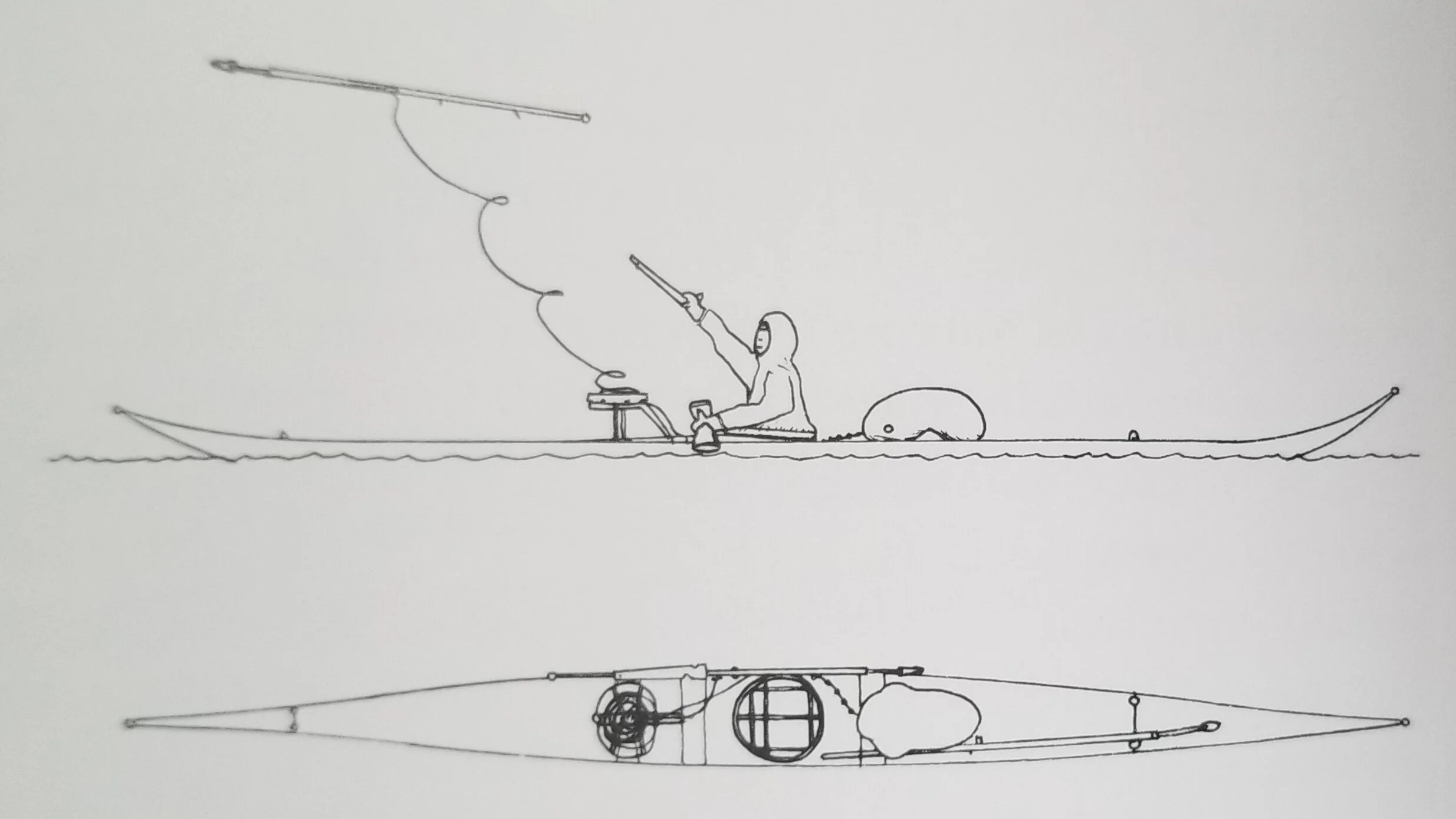

During the seal hunt, the kayakers would position themselves down wind of the seal and paddle toward the seal in a straight line so the animal could not smell them coming. A weathercocking kayak was actually beneficial in these hunts, as it allowed them to paddle harder while steering less. (There was no rudder.) A norsaq was then used to hurl a harpoon into the prey. Depending on the animal, different tips were used.

Harpoon Throw Drawing from Harvey Golden's Kayaks of Greenland

As Europeans began trading with these arctic communities, much of their culture was lost and intentionally erased. Some hunters still used kayaks, but many used rifles rather than harpoons. In this time, kayaking became much less common.

The decline in seal and whale hunting as major resources pushed kayaking to be more recreational. Somewhere along the way, kayaks continued to evolve from seal skin to canvas in Greenland. Other places in the world kayak were being noticed for their elegance and functionality.

Like the arctic communities' kayaks, the new generations of kayakers adapted the designs for the conditions they would be paddled in. Like the original kayaks, designs were limited by the construction materials available and technology. Wood boats were easier to make and more durable than the skin on frame. When fiberglass became more available to designers, that became more common. Fiberglass can be molded into complex shapes and are light weight and strong. Kayaks were being paddled in different bodies of water, but it wasn't until plastics became more common that river boating took off. Rotomolding allows a boat to be significantly more durable when bouncing around on rocks.

Eddy Turn in Deception Pass on an Eight Knot Flood

As human technology has evolved, so have the designs of the kayak. We now have incredibly advanced materials that allow us to paddle waters in places that would have been historically unthinkable.

I will always love how my plastic kayaks bounce off of boulders unphased, the speed and rigidity of my fiberglass boats, and how each construction thrives in different environments. However, the day I had the chance to paddle a handmade skin on frame kayak in Greenland will always be a special memory. That is where it all started.

Harvey Golden wrote fantastic books about the history of kayaking and the designs of the boats. I encourage everyone interested to learn more from him.

I believe the paddlesports industry generally takes pride in the history of human-powered crafts. For example, the original Anas Acuta, a classic fiberglass kayak, was a nearly identical replica of a skin on frame kayak built in Greenland in the late 50s. Likewise, Gearlab reimagined the Greenland style paddle into a modern carbon fiber construction but kept many of Greenland paddles' design features. Most notably mirroring their length recommendations to those of a traditional green stick.

Other companies like Kokatat make drastically different products than the historical equivalent. Goretex and latex make far more reliable immersion wear than skins with blubber. However, every product is proudly stamped with Kokatat, a word coming from the language of the Klamath Tribe, meaning "into the water." The Klamath people used dugout canoes as transportation, collecting supplies, fishing, and gathering food around the lakes and rivers around northern California and southern Oregon. The Klamath were, and still are a people dedicated to nature and water, a trait shared by many Kokatat employees and customers.

I will probably never use any of my kayaks to harpoon anything. Still, I think it is ok for relics of the past to continue to evolve while still respecting the cultural history. Apply these thoughts to life, politics, or social justice any way you choose, however, I am hopeful readers will be inspired to bring together a more diverse paddling community while respecting the past. At the end of the day, I paddle kayaks, but I hope to honor the legacy of the qajaq and the culture it came from every time I do.